- Home

- J. A. Lawrence

Mudd's Angels Page 14

Mudd's Angels Read online

Page 14

"Would you be good enough to explain, sir?"

"And your First Officer. Commander Spock also seems to share your—uh—delusions."

"What delusions, sir?" said Spock, equally puzzled. The two uniformed Medical Service officers standing on either side of them moved closer.

"This tissue of fantasy, about a dilithium crystal shortage, the man Mudd, the British East India Company… Oh, a great loss, a great loss."

Kirk stared blankly at the Commodore, who was apparently serious. Spock frowned. "Do we understand that Star Fleet Command disbelieves Captain Kirk's report?" he asked.

The Commodore sighed. "Star Fleet Command assures me that there is no shortage of crystals, and never has been; that there is only one business listed as based on the planet Liticia; that the whereabouts of the man Mudd are not known at present; and that the Enterprise should be in Sector 78 checking reports of a dastardly Klingon infiltration. And furthermore, it is unthinkable, absolutely unthinkable, that Star Fleet would collaborate with Klingons and Romulans."

Kirk turned to one of the psychiatrists. "Isn't it impossible that the entire crew of the Enterprise, as well as the ship's log, could suffer from the same hallucinations?"

"It is unusual, but apparently not impossible," stated the doctor.

"There's something very much amiss," said Kirk, shaking his head. "You have questioned the others?"

"Your officers and crew confirm your story, Captain… which merely goes to show what an influential captain can do. A great loss, a great loss," said the Commodore.

"You will follow us, please," said a doctor.

Utterly bewildered, Kirk and Spock saluted and turned obediently.

"Captain!" whispered Spock urgently, and pointed. The wall calendar clicked from 6013.4 to 6013.5 as Kirk glanced at it, and then at Spock. "Commodore," said Spock, "is your calendar correct?"

"Certainly," huffed the Commodore.

"Captain, do you understand?" said Spock, slowly.

With dawning enlightenment, Kirk said, "I begin to, Spock, I begin to. The contracts haven't even lapsed yet!"

"That is it, Captain. The explosion of Nubecula Minor not only threw us back in space, but in time."

"No wonder Star Fleet Command says we should be in Sector 78. That's where we were— checking a report of an unidentified armed robot vessel. And unless we can convince the Commodore, and Star Fleet—"

"—the crystal shortage won't be noticed till it's too late, and—"

"—We'll start the whole thing over again!"

The two psychiatrists looked at each other and skook their heads. "This goes very deep," said one.

"Delusions of reference complicated by group acceptance," agreed the other. "A unique case, I believe, Doctor."

"A great loss to the Service, of course." They muttered together.

"Spock, just about now, or very soon, those Coridan contracts must be due for renewal."

"Yes, Captain. It's already too late for Muldoon."

Commodore Blunt's head was turning from one to the other, back and forth, back and forth…

"Spock! Could the Enterprise possibly be in both places at once?"

"I do not believe it is possible for both to exist simultaneously in the same space-time."

"We've got to find out—there may be two Human Mudds!"

"That would indeed be unfortunate."

"Unfortunate? The mind boggles, Spock!"

"True, Captain."

"Commodore, would you be so kind as to check with Command… Can they locate the Enterprise in Sector 78? We should be at or near the planet N'cai."

Commodore Blunt seemed to wake from a sort of trance. "I see why your crew are all as mad as hatters, I have no intention of wasting Star Fleet Command's valuable time with any such idiotic request. Doctors—"

Kirk leaned across the desk. The Commodore moved back nervously. "Sir, with all due respect, if we should by chance be telling the truth, it is within your powers to prevent the immobilization of Star Fleet."

"I don't believe it," said the Commodore firmly.

"Commodore, Star Base Seven is very close to the neutral Zone, is it not? Near the Klingon border?"

The Commodore grew red. "Much too close. Constant vigilance at all times. Dangerous post here, very dangerous."

"In that case, it is very likely that this will be one of the bases whose command is shared for the duration of the dilithium crisis—with the Klingons," said Spock meditatively. "Don't you agree, Captain?"

"Marvelous!" murmured a psychiatrist "Paranoid fantasies as well!"

"Klingons? Here, on Star Base Seven? Never!" cried the Commodore, thoroughly shaken.

Kirk and Spock nodded in unison. Blunt's head too went up and down.

"No! It's not possible. Klingons—on my post," said the Commodore furiously.

"A great loss to the Service," said the other psychiatrist sadly.

"If I contact Star Fleet Command… there would be no chance of Them getting in here?" sniffled the Commodore, getting a grip on himself.

"No, sir. It is our wish to prevent the crisis taking place."

"The thought of Klingons… here…" The Commodore shuddered. "Very well, Captain, we will allow you to contact Star Fleet Command. Under supervision." He gestured to the two doctors. "See that the pris—Captain and the Commander are permitted to send one message."

The psychiatrists nodded and ushered them out. As they were turned over to the security guards, one doctor muttered to the other, "Fascinating."

Spock managed to persuade the Communications Officer of Star Base Seven to send a message to one Lieutenant Spxyx, Vulcan, of the Computer Service Division of the Planetary Supplies Section, Department of Logistics. "For," he said, "if we waste our single message merely asking whether we exist in two places at the same time, nothing can be accomplished with regard to the sabotage of the contract renewals."

Lieutenant Spxyx replied promptly. The computer responsible for keeping records of contracts was indeed unsuspectedly malfunctioning. An unusually interesting malfunction, Spock—technical details would follow—and thanks. Saved us a lot of trouble.

"Don't mention it," said Spock.

"Wait a minute," said Kirk. "We want him to mention it."

"Uh. Mention it, Spxyx—to the Chief of Staff's office."

Star Fleet Command, to its own amazement, had begun to find small evidences to support the Enterprise report. Shipments had ceased to arrive from Muldoon; the faulty computer; and the Enterprise was certainly nowhere to be found in Sector 78. It had apparently winked out of existence, just before the Enterprise had been detected by Base Seven.

"A relief, Captain?" said Spock quizzically.

"One Harry Mudd, Spock, is more than the universe can bear."

Mudd's contracts with Muldoon, via the Galactic Trading Corporation, were of questionable validity, since the incorporating officers were H.F. Mudd, Harcourt Fenton and Leo Walsh. Mudd's personal assets were to be attached to offset liabilities incurred by this company.

The Enterprise had been repaired. Star Fleet's Legal Department advised that actually, the only offense on which there was a hope of convincing Mudd was commanding a ship without a license. The statute of limitations, alas, had expired on his previous offenses. The fine for this sole misdemeanor would be deducted from his assets as soon as auditors had completed working on the books of the Galactic Trading Corporation.

"What shall we do with him?" Kirk inquired.

The Federation shrugged its collective shoulders. They would consider the matter. Meanwhile, Mudd could be returned to his home planet and ordered to remain there.

"But—said Kirk, appalled.

McCoy said, finally, "They didn't say which home planet. Let's take him back to Stella."

Commodore Blunt and the Enterprise parted on terms of mutual relief.

Mudd said nothing upon hearing of his destination. But an hour later was discovered strapping himself into a scout ship in the ba

y, with a packed lunch and an android girl. "Oh, no," he said, "not that. In the name of mercy, not that. If you knew to what lengths I have been forced… Take me back to my house, and good old Patchwork Farm!"

Three days of severe dieting and one hypnotic trance later, they were in possession of the coordinates of Mudd's original home planet.

"This time," said McCoy with grim pleasure, "I find I have no ethical qualms at all."

Kirk, McCoy, and two security guards carried the struggling Mudd to his front door. Yeoman Weinberg begged to be allowed to come along, to complete his thesis. The house was a small stone cottage, set among blue hills, surrounded by neat flower beds.

"Harcourt Fenton Mudd, how dare you come back to this house in such a condition!" screeched his wife. Kirk and McCoy broke into wide grins, as Mudd cowered behind Yeoman Weinberg's concealing paraphernalia. "Get your fat carcass out of my garden!"

"Uh, madam—" began Kirk, "Will you…"

Around the doorway, behind the talkative Stella, a sly, wrinkled face appeared, with snapping black eyes. "Oh—uh, if it ain't Harcourt come back, Stella. I do declare, it has the same expression—lookee, daughter, it's skeert silly!" The high voice cackled. "Heee! Give it a bone, Stella, give it a bone!"

"Mrs. Mudd," Kirk said, "I wond—"

"Mister, will you take this thing off my doorstep? I just washed it. The refuse dump is down the road a mile or so," said Mrs. Mudd.

"But it's your husband, madam!"

"What is? That? Look, Mister whoever-you-are, my mother and me are doing very nicely here, and I'll thank you to get off our property."

The nose of an old shotgun poked through the door. "Heee! I reckon to be a dead shot," crowed the old lady. "Dance, jellybean!" Small shot splattered the ground at Mudd's feet.

"Owwww," said Mudd, dancing. "Arrest them for assault!"

"I don't think she wants him," observed Weinberg.

"You get that skirt-chasing, potheen-soaking, prubstuffing, motheaten, overblown excuse for a billygoat out of here before I—" Stella's mother stuck her head out again, and whispered something to her daughter.

A remarkable change came over Stella. Her expression softened—as much as it could on so harsh a face. Her eyes traveled speculatively up and down, over the form of Doctor McCoy. "You all come in and set down a spell," she said, with a sweet and bone-chilling smile.

"We just want to return your husband, madam," said Kirk hastily.

"Tell him, daughter!" howled the old lady, her gray topknot quivering.

"I'll take that one," said Stella, pointing a bony finger at McCoy, and advancing purposefully.

The little group backed off. "Now, Mrs. Mudd," said Kirk, "Doctor McCoy is not available. Harry—"

"Is he married?" she said, and brayed with laughter. "So am I!"

"Heee!" cackled her mother, who had crept behind them and suddenly thrust her shotgun into McCoy's ear.

Weinberg, with great presence of mind, unearthed his phaser; as Stella dropped, stunned, her mother turned away from the doctor; and then she, too, succumbed.

"Beam us aboard, quick!" commanded Kirk.

McCoy, rather pale, made no protest at the scrambling of his atoms.

Harry Mudd said, "Yo-ho, laddie, I'm free!" He did a little dance, then a little jig, and landed with a thump in the Transporter Room. "And now will you take me home?"

"We can't do anything else," sighed Kirk.

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE SHUTTLE LANDED a large party on Liticia. The Aruhus, Marilyn and the other rescued androids were greeted with signs of pleasure by their fellows—who had suddenly, and recently, missed them.

It is not possible for androids with a central common consciousness to lie to one another. There was no doubt cast upon their story. It led, in fact, to a great deal of activity.

Uhura, who had become fast friends with the Aruhus, went off with them to work on an android song. The android Mudd escorted the party to the house.

"Well, it's good to be home again," said the human Mudd, kicking off his shoes. "Bring food and drink. Hey, Louise, what have you done to yourself?" The girl-shaped android with the long red hair was no longer wearing transparent trousers. She drew a weapon from her neat blue uniform.

"You'll come this way, Mudd," she said briskly. She reached for his hand, there was a click and he was chained to her wrist. "You are under arrest, in the name of the Independent Government of Liticia," she said. "It is my duty to warn you that anything you say will be recorded and may be used in your trial."

"My trial?"

"Court convenes tomorrow for the reading of the charges." She turned to Kirk and his colleagues, and smiled. "Will you follow me, please? You will be wanted as witnesses."

Somewhat bewildered, Kirk and the others trailed along behind her.

"Independent government? What's happened here?" said McCoy.

"We will undoubtedly find out," said Spock. "These are logical beings."

They were ushered into apartments along a cool corridor. Food and drink were brought, but all queries were met with: "It is not permitted to discuss the case outside the courtroom."

"Well, well, well," said McCoy.

The judge, a Mudd-model android in scarlet robes, entered the courtroom—formerly the Throne Room, under the old dome—with ceremony. The Federation flag was flanked by a bright new banner bearing a silver gear on a ground of the colors of the spectrum.

"Hear ye, hear ye!" intoned a herald. "The Supreme Court of the Government of Liticia is now in session. We will hear the case of Liticia versus Harcourt Fenton Mudd. Bring in the prisoner!"

Mudd stomped in, between two uniformed girl-androids, and was seated in a box.

"The clerk will now read the charges," said the herald. "The prisoner will stand."

Mudd lumbered to his feet "What is this farce?" he said.

"Silence in the court," said the herald.

It took the clerk two days to read the charges. He began, "Harcourt Fenton Mudd, human, you are hereby accused of the following torts, felonies and malfeasances: and rolepsy in the first degree, barratry, charlatanry, civil rights violations of the following articles and codes [here followed a list that took up most of the two days], crossing of planetary boundaries for immoral purposes, malversation, peculation, embezzling, pandering and privateering, speculation and solicitation…" and ended with the appointment of the prosecutor and the attorney for the defense.

The prosecuting attorney introduced himself as Clarence, being a special model for the occasion. The defense attorney, one Perry, was rejected by the defendant, who claimed the right to defend himself.

"A fool for a client," breathed McCoy. "But just as well for justice."

"I don't even know what all those crimes are," complained Weinberg.

"Silence in the court!"

The trial itself began at last. The courtroom was filled—the officers and crew of the Enterprise, even those who were not to be called as witnesses, had requested permission to attend.

Clarence, in sweeping black robes, rose to address the court. There was an interruption. "Hey!" said the defendant.

The gavel fell. "Order in this court!" said the herald severely.

"Sorry, your honor. A point of order!" said Mudd urgently.

"We will hear it," said the judge.

"You can't bring any of these charges against me. They haven't happened yet!"

There was buzzing among the crowd. Kirk muttered to Spock, "I knew he'd think of that."

Spock, sitting with folded arms, smiled. Kirk smiled back.

The judge called for order. The room was silent "The attorney for the defense has spoken out of turn, but the point he has raised should be clarified. I call Mister Spock, First Officer of the Enterprise, as a neutral witness for this court."

Spock made his way to the witness stand. He was sworn in. "Do you promise to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?"

"I do," said Spock gravely.

/> "Will you therefore elucidate the concept of the time period in question—for the record," said the judge.

"Time," began Spock, "seems to us to flow forward, like a river. Those of us who travel in sub-space know that the subjective passage of time bears little relationship to the objective coordinates at which we surface. However, it is generally agreed throughout the Galaxy, to accept experienced events as real.

"In this particular case, it seems that a certain period of objective time existed, passed, and was then cut off from the mainstream, so that there was a loop in which the events to be considered by the court did occur. There is no doubt that everyone on this planet experienced those events—either in person, or through the presence of certain units. Therefore, the events must be treated as real."

"I object!" said Mudd. "I can't remember any of 'em!" He sat down with an air of achievement.

"Perhaps the court will refresh your memory." said the judge. "Thank you, Commander Spock. In any case, let the defendant understand that his memory is not only incompetent, but irrelevant and immaterial. The court wishes to acknowledge its gratitude to the accused, however, for introducing it to the stimulating exercise of the Law." Mudd looked surprised.

Clarence began his address. "Your honor, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, you see before you coram judice the human Harcourt Fenton Mudd, perpetrator of the fiendish crimes hereuntofore enumerated, whose guilt will be proven, quod erit demonstrandum. This entrepreneur of iniquity, unsatisfied with his endless violations in personam of the civil liberties of our sovereign people, did knowingly and with malice pro pense operate his loathesome trade in barratry; to wit, he operated his vessels of shame without a license. Thus, even the very processum of transporting our free people into abject and squalid servitude, did he—"

"Objection!" cried Mudd. "This prosecutor is slanderous, libelous and insulting. He's prejudicing the jury with every word!"

"Objection overruled," said the judge calmly. "That's his job."

"… In barratry, your honor, ladies and gentlemen, the misuse of sacred trust in office, this master of the foul slave-trade did—"

"Objection!" shouted Mudd. "It's not possible to commit misuse of office if one is not in office. I couldn't have been legally master of the ships— I didn't have a license. This charge should be reduced to a misdemeanor!"

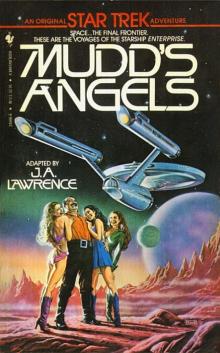

Mudd's Angels

Mudd's Angels